Francesco Poli

A GLOSSARY FOR UGO NESPOLO

What follows is a sort of brief 'glossary' whose purpose is to provide answers to the main queries observers of Ugo Nespolo's complex and varied works may have.

The sequence of the glossary terms and phrases-or reading notes-is not systematic (it is only partially chronological), but rather based on the inner mental process of the artist's exploration -an exploration which has developed in time in many directions but has always maintained its extremely coherent identity. Therefore, each term or phrase connects to others, thus developing a network hopefully aimed at producing a satisfactory global picture.

Puzzle

Since this glossary is to some extent a puzzle, it is inevitable to begin with this term.

In many ways the interpretation of Nespolo's works seems to be fatally bound to this term, which was first used by the artist himself when he gave the title The Logic of the Puzzle (Galleria Il Punto, Turin, 1966) to one of his early exhibitions, and has since been used by all critics, who have always stressed the playful aspect of the term's meaning.

Let us begin with the vocabulary definition of 'puzzle': "A game consisting of irregularly-shaped cut out elements which must be joined together in order to reconstruct an image (drawings or photographs of easily-recognized subjects)". The more the pieces to be assembled, the more complicated and interesting the game becomes to puzzle enthusiasts, who are not driven by aesthetic results (the attractiveness of the image is not of major importance) but rather by a strong, and sometimes obsessive, need for tidiness-the desire to transform a chaotic and incomprehensible pile of small fragments into a perfectly structured whole which is clearly defined from an iconiccomprehension standpoint. It is, in other words, a work of patience and determination based on an observation and selection which creates nothing but consists in putting all the pieces back in their designated place. Like crossword puzzle and rebus buffs, the puzzle enthusiast wants to find 'the solution'- the one established beforehand by those who created the puzzle. This is the 'logic of the puzzle', which does not accept alternative solutions, polysemous ambiguities, or highly-imaginative suggestions insofar as it is a closed and 'perfect' system.

Quite different is the 'logic of the puzzle' which emerges from Nespolo's operative and creative practice, which definitely possesses a playful quality but branches in a different direction and has ironic, and even enigmatic, characteristics that destabilize the standard vision habits and invite the viewer to read the works with an unconditioned and imaginative eye. It is not by chance that the artist is an initiate of Pataphysics - the science of unreal solutions.

It is important to specify that the main meaning of the word 'puzzle' is some-thing that baffles, perplexes, bewilders, or intrigues. This definition also applies to the artist; standard puzzles cease to be interesting once they have been completed, whereas the artist's figurative means are open a problematic because they are aesthetically stimulating.

These works, apparently easy and pleasurable to comprehend, become a more attentive and meditated vision-something which is more intriguing and complex, and plays on a sophisticated dialectic between the structuring and de-structuring of the language of visual representation. Nespolo's invention was to employ the puzzle technique as an unexpected and surprising form of art which questions even the common procedures for image-based paintings.

The initial cultural context of this operation was that of the early Sixties Pop Art experiments. The characteristic of Pop Art is not only to choose subjects and themes linked to a mass-culture iconography but also to employ impersonal and stereotypical styles and techniques such as those used in graphic design for advertising, aerograph-painting posters, comics, and photo-serigraphy.

According to the critic Robert Rosenblum, "A true pop artist makes style and subject coincide. The

artist represents images and objects in limited editions by using a style which is also based on a plastic vocabulary and on the techniques employed in the production of limited editions."

Initially fascinated by the playful stereotypical freshness of children's colouring books (those with outlined figures to be filled in with colours), Nespolo was the first artist to use puzzles to create invented or re-elaborated images based on pre-existing models. The use of this technique (not for the production of a limited edition but for exclusive works) is quite original, as the challenge represented by the game is not as important as the visual appeal of the combination of brightlycollared wooden puzzle pieces. What emerges from the first stage is a child-like dimension staged with amused irony. But later on, things become complex as new themes enter the scene: word games linked to visual-poetry, and sophisticated citation strategies-especially those aimed at reexamining the history of modern and contemporary art. For Liechtenstein the banal comic-strip style and even the half-tone screen become elements of a sophisticated personal style when elaborated to produce works which also have complex meta-linguistic qualities. Similarly, for Nespolo the puzzle becomes a specific and unmistakable style, which significantly affects structure, signifiers, significances, form, and contents.

Pop Art in Turin

Nespolo's puzzle-compositions, with their synthetic and imaginative pictorial nature, are without doubt the best contribution to Italian Pop Art, albeit, as mentioned previously, they later developed different characteristics.

It is worth recalling that in Turin, during the mid-Sixties, the post-informal turning-point in the direction of Neo-Dada and Pop Art was amongst the quickest and most interesting. Although there was no true Turin Pop-movement (such as the one in Rome, formed by Schifano and friends), many are the artists who have been stimulated by this new cultural milieu, amongst which Antonio Carena, Pietro Gallina, Beppe Devalle, Giorgio Bonelli, and es-pecially-in very original terms which foreshadow developments in other directions - Aldo Mondino, with his ironic painting games, Piero Gilardi, with his 'nature rugs', Alighiero Boetti, with his works of genial and lucid conceptuality, and to some extent Michelangelo Pistoletto, with his mirrors and 'less-objects'. Nespolo and Mondino - but especially the former and Boetti - share the same particular playful and ironic vein.

Beyond Pop. Tangencies with Arte povera

Right after the explosion of Pop Art, Nespolo was amongst the protagonists of the extremely-vital avant-garde in Turin who was in close touch with the emerging exponents of the Arte povera [Poor Art] movement.

His creative domain extended beyond painting and branched in two directions: the production of experimental films (one of the most important aspects of his exploration throughout the decades which follow), and the creation of objects-constructions and installations made with rather poor material-which continued to have that ironic and paradoxical quality, but also a specific conceptual value.

This is especially the case of the Conditional Machines and Objects-a large production of objects created in 1967 and displayed in a personal exhibition at the Schwarz Gallery in Milan in 1968. At that time, these were Tommaso Trini's comments on the exhibition: "[...] Nespolo focuses on the purpose of objects rather than on the objects themselves. He has invented 'pseudo-materials' which add artifice to the artificial. He has built a machine that transports air and a telephone that communicates the buzz of its internal power: electricity. He has arranged space by using metal bars laid in an I-beam manner, and with the same bars he creates environments featuring obstacles.

[...] A parallelepiped made with stacked wooden boxes is reminiscent of a primary structure, but then we see the carpenter vices, the attached tools 'for making', which turn the formal data into

constructive references. Or we see a ribbon that secretly and inertly meanders between two containers, where it could be rolled up or rolled out, if we chose to manipulate this game-sculpture [...] To Nespolo the act of constructing therefore means entering a mechanism based on action and reaction. Between picking up wicker baskets, ping-pong nets, compressed card or card arranged like files, and the function of the new object, he is interested in the moment of transformation, from possessing the object to using it. He emphasizes learning about things."

In another exhibition (Il Punto, 1968), a spectacular installation was displayed-Molotov.

It consisted of hundreds of bottles with wicks, neatly placed in diagonal storing structures. It was a provocative ephemeral monument dedicated to the 1968 political struggles, perhaps with an implicit reference to Duchamp's Bottle Dryer. A great deal of these works are not far from the same wave length of more minimal works which his friend, Alighiero Boetti, was producing, such as Ping Pong, Mimetico, Rotolo di cartone[Cardboard Roll], Catasta[Pile], and Lampada annual [Annual Lamp], displayed in his first personal exhibition at the Stein Gallery in 1967.

Even though the artistic aims are obviously different, as regards the use of craft techniques, there is yet another affinity between the two artists: Boetti's tapestries (weaved by Afghan and Peshawar women)-for example, the world maps and the letter and word games-and Nespolo's puzzles and other works realized with words and images and with different arts&craft techniques.

Boetti himself in a conceptual work, printed as a poster and realized in 1968 presented a list of 16 friends which comprised all the Arte povera artists: Ceroli, Schifano, Simonetti, and Nespolo-each accompanied by a cryptic judgment written with absolutely indecipherable symbols. In 1967 Nespolo participated with many of these artists in one of the fundamental turning-point exhibitions, Con/temp/l'azione (in the Christian Stein, Il Punto and Sperone galleries).

And, the realization of three art films on the works of other artists: Neonmerzare (1967), Boettinbianchenero (1968), and Buongiorno Michelangelo (1968â69), consolidated the close relationship with the Poveristi. It is an extraordinary example of avant-garde experimentation open to the most vital and stimulating interdisciplinary experiences (plastic arts, theatre, and cinema).

These works too bear witness to the artist's preference for metalinguistic operations in the area of interpretation, rereading, re-examination, and citation, whose themes are works of strictly contemporary or modern art by other artists.

Dada Fluxus

"L'art est inutile. Pas d'art. A bas l'art". These sentences were written on a sign which Nespolo held during a performance staged with Ben Vautier at the Gallery of Modern Art in Turin in 1967. Along with Gian Emilio Simonetti and Giuseppe Chiari, Nespolo is one of the few Italians who participated in the actions of Fluxus-an international movement characterized by the greatest degree of expressive freedom, by an interdisciplinary and multimedia character, by the rejection of any traditional formalization, and by a close relation between art and life.

Worthy of quoting is the provocative 'portrait' which Ben Vautier dedicated to his friend: "Nespolo / est ambitieux / Nespolo / est jaloux / Nespolo / est hypocrite/ Nespolo / est méchant / Nespolo / est menteur et rusé / Nespolo / est devoré de / prétention / C'est un loup / Il se porte bien".

This radical experience, despite it was short-lived, contributed to the evolution of a counter-current attitude of ironic freedom, and to a Dadaist vision of art ('anti-art')-enemy of all pedantic seriosity-which has developed in the most destabilizing forms, especially in his film-making activity, but has also left profound and lively traces in his production of paintings and sculptures.

Still in 1977, at the venue 'Dov'è la Tigre?' [Where is the tiger?] in Milan, he organized a spectacular game-based event-a sort of interactive happening consisting in a bizarre amusement park with different kinds of games in which the public actively took part.

Pataphysics

A specific connotation of Nespolo's Dadaism is connected to the 'science of imaginary inventions', invented by Alfred Jarry. His character, Dr. Faustroll, is a great master of these inventions. The College of Pataphysics was established in 1948 in Paris. It had numerous filiations, amongst which the Milan college founded in 1964 by Enrico Baj. Nespolo joined Baj and later found- ed the Turin section. In 1972, he and Baj open the Premiato Studio d'Arte Baj & Nespolo in Milan.

The Pataphysic spirit is characterized by an attitude which is fantastic, anarchist, ironic, sarcastic, liberating, open to paradox and to creative provocation, and animated by a distinct inclination for the mockery of every form of conformism and middle-class respectability.

As examples of Nespolo's Pataphysical forma mentis, we can quote an extract from a text published in a catalogue in 1974 (Galleria Blu, Milan).

From Biobibliografia (divided in three parts, 'Nato' [Born], 'Crepato' [Died], 'Campato' [Lived]): "Nato: Pappato Rognato Caccato Dormito / Il babbo veloce lo dice al cognato / Precorre Istintato Mostrato col dito / Artista sicuro Ben ricco impegnato [...]."

Words and Images: Game and Double-game

Nespolo's game-dimension moves in a brazenly childish direction-but also in the direction of sophisticated linguistic and iconic lucubration and sarcastic critical provocations towards ideology and the contemporary art system- often takes shape via a well-articulated interaction between written text and formalization on an artistic plane, realized with wooden puzzle pieces and other techniques and materials, such as alabaster inlay and embroidery.

Although in absolutely original terms, this part of Nespolo's work can be connected in some ways with a research area which goes by the name of 'visual or concrete poetry', but with a very particular connotation characterized by a priority interest in visual quality and which is quite far from the critical intellectualism and sociologism of the exponents of that trend.

Nespolo is first and foremost a painter who manages to transform words and sentences used in his compositions into elements of undoubted visual fascination (as Magritte or Boetti, albeit in a very different way), but he however succeeds in keeping alive a meaningful tension.

In this respect, perhaps the best interpretation of Nespolo's complex visual verb game-dimension is the following highly-cryptic text by Edoardo Sanguineti, titled Rompilingua Scioglitesta[Tonguebreaker Head-Melter] (presentation for the exhibition catalogue Ugo Nespolo nella più bella mostra dell'anno, L'Atelier, Turin, 1970), from which the following quotation is taken:

"Un Giuoco Oscuro Non à Scurato Per Oscurare L'Oscurità Un Giuoco Ondoso Non à Sondato Pen Ondosare L'Ondosità [...] Un Gioco Oblato Non à Sublato Per Oblatore L'Oblacità Un Giuoco Osceno Non à Scenato [...]"

The Poetry of a Citation

One of the most characteristic aspects of Nespolo's exploration, and perhaps indeed the fundamental one, is his declared dislike for the legend of creative originality and of the 'work of art', and also for the avant-garde rhetoric of the ongoing innovation and invention of new languages and styles. His stance is a very particular and interesting theoretical and operative one, as it is consciously contradictory and provocative. Allow me to explain. Nespolo is an artist of unquestionable creativity, and his training during the Sixties is closely connected with the avantgarde research (Neo-Avant-garde) in an important cultural context such as Turin's, which he immediately became part of and in which he occupied a high rank. Therefore, like almost all of his companions in the venture of that period, he could have evolved in that direction.

However, in the early Seventies he decided to re-shuffle the cards and place himself in an out-ofline position with respect to the breaking of the programmatic mould of the new minimalist,

processing, poor-art, and conceptual trends.

This very early decision - which has specific port-modern values-has counter-current characteristics, as, albeit it is based on a true conviction of operative freedom, it also claims a sort of 'return to the trade' of dechirican memory; in other words, a return to the production of quality artefacts made with techniques which are not avant-garde but are connected to the arts&crafts techniques in an innovative way.

Quote/Copy

Hereafter is the exact declaration of praise of the copy, titled A coloro che si sentono copiati (con la mania dell'invenzione) [To Those who Feel they Are Being Copied (and are obsessed with inventions)]: "INVENTARE / INVENTARE / INVENTARE / ma che cazzo sognate di fare / La regola sia invece / COPIARE QUANDO TI PARE / (questo sì che è inventare) / ecco cosa si deve fare" [INVENT / INVENT / INVENT / what the hell do you dream of doing / Let the rule be, rather / COPY AS MUCH AS YOU WANT / (this is indeed inventing) / this is what one should do] (in exhibition catalogue Galleria Blu, Milan, 1974).

Quality Art. Art&Crafts Techniques. Postmodern

While Nespolo continued producing experimental films (not many, but consistent throughout the years), as of the early Seventies, his figurative art production developed specific contours and he intensified his production of puzzle compositions, but also of works realized with materials and techniques specific to the crafts field, with ever-ironic and provocative intentions.

L'avanguardia punto dopo punto [The Avant-garde in Detail] (exhibition in 1973 at the Galleria Blu in Milan), is an example of an irritating citationism which scoffs at the avant-garde by transferring onto embroidered silk a series of works by innovative artists such as Noland, Morris, Warhol, Liechtenstein, and Gilbert & George. This operation could be defined as 'retrò-avantgarde' and it is the prelude to a large production of puzzle-works (including highly-impressive compositions) which displayed citations from works by major contemporary artists and by the historic avantgarde.

The following year the same gallery presented a personal exhibition which Paolo Fossati, in the catalogue, ironically referred to as 'rich art'. The exhibition title itself, Ugo Nespolo. Alabaster, silver, ivory, ebony, lacquer, silk, and glaze. stresses in a provocative manner the display of the precious materials used for works produced with painstaking craft skills. The exhibition also displayed small classic temples filled with small objects. The temples were definitely post-modern and ahead of their times, and their style can be described as Pop-Decò.

A further consideration is appropriate at this point. These works, besides their unquestionable pop connotation, can also be connected to the marquetry tradition, especially Renaissance marquetry and specifically wood-marquetry, which was often the work of marquetry-masters who based the decorative schemes on cartoons by great artists.

During an interesting conversation with the artist, the philosopher Gianni Vattimo said he was impressed by the evidence of his "mastery in composition and even manual work" (and by his particular ironic pre-postmodern vein), which in many ways was expressed through "the rediscovery of shapes, even the traditional ones", albeit in a manner which is not at all traditional. He also justly stated: "You have every right to claim for yourself a post-modern sensitivity in times in which a modernistic avant-gardism still dominated" (in Ugo Nespolo, exhibition catalogue Palazzo Reale e Arengario, Electa, Milan, 1990).

Museum Stories

"I love using the arts warehouse as a source of inspiration, as it were, and also 'the surrounding reality'â¦" Museum stories is the title of an attractive book (Marescalchi-Allemandi, Bologna, 2001) which documents most of the large production of puzzle-works dedicated to the fascinating, alienating, and fetishist theatralization of modern and contemporary art displays, joined like pieces of a large cultural puzzle. These puzzle-works are the highest expression of a mocking and bulimic citation strategy program, whose polemic objective is not the artists' works (in many cases loved, and in any case always respected), but the way they are displayed, at the service of an alienating and pseudo-elitist 'aesthetic enjoyment' which is useful to the art system and more generally to the show-loving society.

Nespolo's operation in this case is not to be interpreted reductively, that is, only as an intelligent, witty, playful, provocative tour de force (as too often the non-favorable critics have described it as being), but also as a testimony of a true love-hate feeling for a condition which drastically affects the destiny of artistic creativity.

Therefore, we should trust Nespolo when he says that this operative attitude of his-ironic, at times sarcastic, and with a liberating function-also has a tragic connotation.

"If you think about it," the artist said to Vattimo during the previously-mentioned conversation, "there has got to be a sort of tragedy in the 'game' I have always set up for the purpose of bringing an element of ironic doubt to 'modernity', as can be seen in the museum exhibitions in which I elaborate images that show museum halls (more or less imaginary ones) and their works reduced to picture-cards."

In the book's introduction, he wrote: "This book recounts the many stops along a unique journey in which the puppet-theatre of art is represented with all its protagonists: the empty box/museum, the work/mute protagonist, and the spectator/shadow."

This provocative position is supported in the book by many quotations by writers and philosophers, especially by a series of ruthless considerations on the art system in New York by Tom Wolfe- author of the famous pamphlet The Painted Word (1975).

Having said that, we cannot help but appreciate, even with amused pleasure, the figurative quality of his complex, articulated, fantastic, colourful composition-games in which the works of celebrated artists are re-examined and reinvented with unconventional precision (beginning with the direct knowledge of the original linguistic solutions) and placed in relation with the display halls and the presence of the visitors in such a way as to generate sophisticated iconic stories with a common style. Here everything becomes 'Nespolized', if you will, as in a huge card game, where instead of the kings, queens, and jacks we find the art-history version of the loved, collected, and mocked Panini picture-cards.

Nespolo brings out into the open the liberating attempt to neutralize the basic contradictions through the game-entertainment strategy, intentionally elaborated on a dual and ambivalent register: a provocative regression into childhood, and the au duexième degréof a sophisticated metalinguistic operation.

I use the term 'attempt' because the risk (indeed aesthetically productive) is ultimately that of entering a labyrinthic reality which has no exit. But this is perhaps the inevitable destiny of art.

Nespolo's

The polemic attitude towards an art system becomes even more provocative when the art market too is directly at stake. In this respect it is the founding (in 1993) of 'Nespolo's Società in proprio' [Nespolo's Single-ownership Company]-and operation staged by creating a series of puzzle-works which look like images from the page of an auction catalogue which document as precisely numbered lots, works by various authors, from Dubuffet to Larry Rivers, from Appel to Baselitz, and from Warhol to Twombly.

Fortunato Depero

The artist most loved by Nespolo is Fortunato Depero. He was an extraordinary protagonist of the Futurist movement who has until now been rather underestimated because guilty (for the conformist historians and critics) on the one hand of not having taken into consideration the canonical separation between 'pure' art (painting and sculpting) and applied arts-and for this reason accused of being more of an artist/craftsman than an artist, and at the most a proto-designer-and on the other of having been too superficial, considering his fantastic and lucid irony. Essentially Depero was not taken too seriously (not even in his times, which were dominated by 'true' artists such as Sironi and Carrà ), and he was placed in a marginal position.

However, Depero was a great precursor of an open and free conception of wide-spread and multidisciplinary artistic creativity. In his highly sophisticated yet naïf geniality, he was a very original painter, sculptor, set designer, designer of objects, and graphic designer who always worked pursuing his (and Balla's) utopian dream of a "futuristic reconstruction of the universe" with an extraordinary creative energy.

Nespolo's admiration for Depero (whose works and writings he passionately collects) is a clear statement which aims at affirming a different and alternative definition to the dominant one, of the contemporary artist 'fit for a museum'.

In many ways Nespolo sees in the artist from Rovereto a model to refer to, albeit he is quite aware that the times have changed and the avant-garde utopia must be replaced by a concrete, operative, and professional pragmatism, without, however, necessarily abandoning the freedom to be unconventional and pursue new creative experiences.

Collectionism

In his elaborate and complex artistic practice of citation strategies there emerges a unique collectionist syndrome, for creative purposes, which is under firm control.

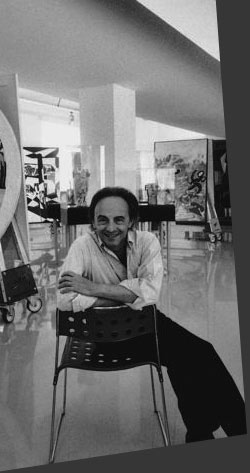

It is not by chance that this passion has evolved, for the sake of enjoyment and cultural interest, into collecting objects which end up animating his spectacular studio in a very distinct way. The collections include paintings and sculptures by his favourite artists, pop objects (Renzo Arbore would be very jealous), film cameras and projectors, rare books and other published material on contemporary art. All this is closely connected to Nespolo's own works, and thus shapes an interior landscape which is to a large extent the artist's interior landscape too. In this respect the studio is a concrete extension of the mental landscape of the artist-something which is actually true of all authentic artists.

The photographic book by Gianni Berengo Gardin, Dentro lo studio [Inside the Studio] (Skira, Milan, 2003) magnificently documents what has been stated.

(From the book: Nespolo Ritorno a casa. Un percorso antologico, Museo del Territorio Biellese, Biella, 2009, Silvana Editore, Milano)