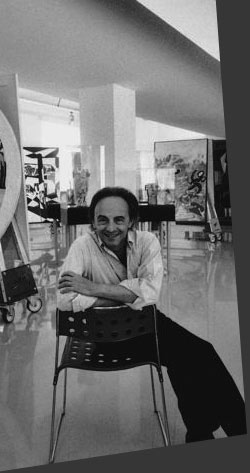

Furio Colombo

AN AMERICAN INTUITION

In spite of appearances, Nespolo must not be seen as a figurative portrayer of the real world. Due emphasis must be placed on his atmosphere of play and his sounding of the tones of fable. Nespolo makes use of shapes (shadows, outlines, silhouettes, figures of human beings, spatial definitions interiors) in the way Calvino employs words, a deceptive realism laboratory-concocted for a genre necessitating a high degree of artifice. We are aware that Calvino's mind is a landscape of notions camouflaged with narrative. For him, story-telling is the liaison, the train of which the story rides, even though this story is not one of happenings.

Nespolo's figures are the components of an experiment that an instinctive graciousness clothes with the form of a game, cleanses, and classifies in an unswerving search for perfection. Yet the operation is not more complicated than this. The "jigsaw puzzle" - a technique with which many of his stories are constructed - should serve as the initial revelation. Assembly is all in Nespolo's world, and the choice of this expedient also marks out for us the bounds that the artist imposes on his own freedom - the rules of the game, as it were.

The puzzle, then, is both an arbitrary pathway, since Nespolo is its author, and an obligation, since the decision that pieces are to be interlocked imposes completion of the puzzle with scrupulous attention. This sets the yardstick by which to measure the coherency and consistency, or, if you will, the morality of Nespolo qua artist: he follows strict rules in composition yet composes within the bounds o f a puzzle that he himself has constructed. His feather-light touch is that of one who appears to believe that a game can be made out of anything. A premiss, however, that is apparently belied by his painstaking, even obsessive execution. That same light, frivolous touch, the smile for his public, and his accomplishment of seemingly weightless gestures conceal acrobatic labours performed with mathematical accuracy. In a game such as this, the course is sown with an infinity of tricks and hazards, but not the finish. The end is total success, or total failure. Because he succeeds, and continues to smile at his public, Nespolo continues to attract attention. And such attention engenders a necessity to know more about him. What, for example, are his relations with the other visual arts? Like his contemporaries, Nespolo looks to the cinema and photography. To be more precise, he thinks in terms of the single frame, the frozen instant o f a whole sequence. His combined desire for composition and movement requires that the subject, be it image or vision, be alive. Here, perhaps, the critic may advance a word of clarification. It is not so much the cinema that enchants Nespolo, though his practical experience as a film-maker is well known, but the theatre. And not in its practical form, but as the theatre concept which imbues that first instant when a scene is unveiled, its lights a mite too strong, and the leaps and bounds between its contrasting nearnessâs and closenessâs, and its pools of light and pools of shadow.

The wonderment of it all. This enchantment has caught the fancy of many Europeans, from Wedekind to Körmendi, and can equally be espied in the detailed grace of Vienne Moderne and the scale models of buildings, cutaways and interiors of the Bauhaus. With Nespolo, however, there is something more to add to this enchantment. His surfaces, for instance, are smooth, polished like those o f a toy, with the perfection needed for the performance of a function of extreme delicacy, such as the penetration of spaces gauged with both strictness and gentleness. Art as the machine whereby art (i.e. beauty) is manufactured is a well-rooted tradition in Nespolo's artistic memory. If anything, this has an air of the curious about it, an dis worthy of critical attention. There is a leap of the part of two more desperate and Latin generations in the search for a new beauty. There is an eye kept, even in the technique used in his manufactures, on a certain "modern" Europe. Then there are the lines along which directs his search for forms and composes his collection of images. Freeimages, these, tender and frivolous, up to the point where closer inspection reveals the relation between the artist and his materials, his vision and the instruments for its realisation. By retracing the sequence of motivating forces and gestures that can be glimpsed in his works, one reaches the point or moment that a romantic (or a psychologist, with other things in mind) would call "inspiration".

Nespolo's "American period" is marked by stronger lights and wider spaces. It provides a good observatory of his modus operandi. Enchantment has made way for a labour that calls upon the services of two ingredients: craft and memory, that is to say, simple faithfulness and complete inventiveness, the recording of what is and what is imagined. At this point, account must be taken of another fact in Nespolo's world. Plain indeed is the conviction (itself both a game and an obsession, or play as the release from obsession) that everything is contained within something else, one providing a spectacle for the other, and that the author knows only too well that he is both actor and spectator at one and the same time, creator of one theatre and part of the show in another, an instant in a sequence that would be joy full were it not perhaps also mysterious, difficult to govern, making a continuous demand that effort be expended in a double or triple performance (as actor, director and member f the public). Hence that obsession with detail, that passionate desire for the finishing touch that many (benevolently or otherwise) regard as his artisan trait, which probably depends - if this view of the matter is correct - on his unwillingness to trust the part o f a spectator that he cannot control. Perfectionism, therefore, is a Lebensphilosophie, a gesture that is both humble and grandiose indicating one' s placement in this intricate series of tiny theatres. Since Nespolo masters his obsessions (and here lies the difference between madness and art), and since he knows that he must be their servant, his exorcism takes the form of setting the stage in his theatre and presenting it: the picture within the room, the room within the museum, room, picture, occupant, and museum within the city, and even the city itself as an interior. Here, then, lies the strength of his American intuition.

With one of his light somersaults, fraught with difficulty and simple at the same time, he accomplishes with a single gesture the work o f a collection of studies, researches, and statistics: the city as an interior, the road footpath, the carhome, the could-tent, and skyscraper-decoration...

The game is not yet finished.

(From the book: Un'intuizione americana, Edizioni Luisella d'Alessandro, 1983)