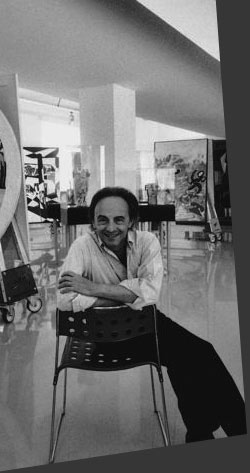

Gianni Vattimo

L'OEUVRE: A WAY OF LIVING THE EXPERIENCE OF MORTALITY

Conversation between Gianni Vattimo and Ugo Nespolo

G.V . That which, l must say, always strikes me and, in my opinion, sets the seal on your work and your image with respect to that of other artists (those I'm familiar with, of course, and l can't say I'm au fait with all and sundry) is a distinct mastery, manual as it were, in the realm of composition.

A strong swimming against the tide, l feel. Mulling it over, though without wishing to generalise, l believe one of the leitmotivs of contemporary' art is the predominance of invention over execution. You get the impression that a work sets itself up as a poem, repeated in a variety of keys, where we the uninitiated - one has to say this - can cast our eyes, but register precious little. Take inimitableness, for example. I've always wondered, and l know I'm partly barking up the wrong tree, whether you can really tell a genuine Fontana from a fake, a real Buren from a homemade version. One can go the whole hog and say that even a Mondrian suggests that we're dealing with the do-it-yourself brigade. Of course there are techniques for weeding out the sheep from the goats, yet l get the impression that for the most part there is a need in contemporary art to hit the mark with a hallmark of style, which does not necessarily correspond to mastery in execution, something close to the idea of a trade mark.

U.N. All my work is certainly bespoke tailored. Yet l never regard technical skill as an end in itself. I do claim, however, that l treat it as instrumental to the "thought" below the surface.

G.V . Fair enough, yet what you do tends to throw me. Powerful execution, according to me, is one of your qualities, one of the traits that distinguish you, but for one like me with an intensely ideological experience of contemporary art on his back seem to constitute a sort of limit. A limit that l personally, l don't mind telling you, have stepped beyond via examination of the post-modern. It seems to me, in other words, that for some reason to which l can now attach a very theoretical connotation we have bidden farewell to the weighty load of irony characteristically heaped by modern art on visible forms and traditional institutions, including mastery of execution.

U.N. l suppose you mean by irony the short cut l constantly use as a means of access (though not as a diving-board) to the world of already "known" forms, even to the sphere of the "traditional", through the trick of "quotation".

G.V . Let' s say that this ironical attitude on the part of modernity, l mean this attitude of continuaI allusion to another way of getting to the heart of things, is so "alter" that naturally nothing but a negative expression is possible: the Silence of Beckett according to Adorno, et cetera. I believe I have only reacquired the ability to appreciate your work through this sort of post-modern liberation with its harking back to even' traditional forms. There's not much of the traditional in your work, of course, but by comparison with the "purity" of a certain conceptualism rampant in the Sixties we are on the threshold of post-modernity. You could rightly claim a post-modern sensitivity in the days when modernistic avantgardism was all the rage.

U.N. You may find it odd, but this claiming an idea! kinship with groups, movements or mere currents of taste seems to be part of my horoscope. At an exhibition held in the mid-Sixties at the Galleria Schwarz in Milan, I exhibited some works that were decidedly protoconceptual, as Tommaso Trini

and Lea Vergine remarked, so much so that I then joined the hard core of poor art painters and 'took part with them in a number of exhibitions in Italy - "Il percorso" organised in Rome by Germano Celant in Rome, for example - before poor art received its official credentials. Since then, however, and quite apart from the fact that I can't stand guided groups, I have directed my efforts to better execution, an innate yen for "the job well done".

G.V . Yes, and alongside this let's call it manual, executive feature, what once again strikes me in your pieces is a psychological trait, a sort of interior attitude, as it were. There wouldn't be, how shall we put it, this accuracy of execution if there were not an all-in-all affectionate attitude towards objects. This, too, is very significant in my opinion, since I believe certain formal styles offer no alternative to apocalyptic art.

I've never come across a twelve-note opera buffa. Maybe there arent't any, or at any rate they're not often staged. Generally speaking, a dodecaphonic opus is one we can readily relate to concentration camps or at all events the tragic drama of contemporary man, whereas opera buffa, for me, means Rossini or a chip off that particular block. An avantgardist attitude doesn't leave much elbow room for a psychological rapport with reality that smacks of positiveness or readiness. One reason being that when seen through the ironical perspective of the avantgarde the real is always a false real, a chopped in half, shrunken real, an apparition to be transcended.

In your case, however, it's a pleasure to recognise traces of the real, of "things" every now and then.

U.N.

I 1ike to use the storehouse of the arts as a source of inspiration, as it were, and that includes the real around us.

G.V . It's you that tells me there are sometimes things you remember from journeys âlittle menâ, much like those we'd been made accustomed to by a certain avantgarde (the early Klee, Kandinsky, etc.). And that's not all. I find there's a sort of return to âsimplified formsâ handled with an attitude, how shall I put it, not of violent searching for the essential, but of affectionate embracing of things that in this perspective ease to be monumental and acquire a different nature composed of features that are not essential as the metaphysicist understands the term, but confer liveability, frequentability. Your world, indeed, is relatively more frequentable than that of other painting.

The importance of this lies in the fact that it is now, perhaps, one of the few ideas I believe I have with regard to aesthetic experience. After teaching aesthetics for so many years, I have set about the process of simplification and weeding out. One of the few notions I think I have concerning aesthetic experience leads to the concept of the inhabitability of a world, that is to say the idea - in broad, positive terms - of art as decorative: construction of décor as the setting for the stage on which life is acted out.

Now this is undoubtedly a - once again post-modern - harking back to certain traditional forms of poesy, since inhabitability was not the main aim of the avantgarde.

It would be closer to the truth to say that the avantgarde was out to throw things off course. A necessary component of experience, I agree, but one that, now for a variety of reasons linked to all the theoretical background under1ying the assertion of postmodernity is quite simply not what we are after. We are more anxious to find a form of inhabitability.

Perhaps there's something to be said for the view that we're not, as Omar Calabrese has said, in a NeoBaroque age, but, as I see it; a Neo-Rococo age shocking thought, but there it is! What I'm saying is that all the tragic side of Baroque that formed the foundation of Benjamin's essay, and has nurtured a certain Benjarninism in recent decades, ends up embedded and somehow dulcified within a perspective that is not so much a trompe-l'oeil!, as might spring to mind from all those rocailles, as a perspective seeking delicacy, as in the Court Theatre of Munich, the city that perhaps best espresses this concept. I know as well you do, of course, that the first birth whimper of Nazism was heard in Munich, but that's neither here nor there for Neo-Rococo. You can hardly blame a city for all that goes on within its walls.

I'm not trying to say the tragic's been pushed under the carpet. No, it's been carried over into a

constructive, conversational setting where building and dialogue also demand a certain detachment, a soupçon of formality. I'm not very well up on the history of Rococo art, but its spirit interests me. Even Mozart's popularity in our culture rests perhaps more on Mister rather than Maestro Mozart, not the Mozart of Amadeus, but that of Pupi Avati, a sort of anti-Amadeus of a kind more intimately rococo in the sense I used before. Not the great tragedian who gives us the statue of the knight at the end of his Don Giovanni, but the composer who conceals the tragic in music whose formal perfection is not just superficial but cultivated and rendered with affection.

U.N. What you've said really ties in with my modus operandi. Many of those who have written about my work have concentrated much or all of their attention on features illustrating an "absence of the tragic", if you will, so as to bring out the conclusive aspects of the "well done", well finished, or even "well designed". I have always claimed that there's a "painful" side to the supposed "educated" game, an attempt to get round the impossibility of creation (in the Mannerist sense) that realises the enormous, almost insuperable barrier of creating anything "new", on the one hand, while on the other hand I've built up a kind of perennial intolerance of the dictates of creation to order amid the rank and file of fashion's whims. If you think about it, a tragic note of some sort must also run through my endless game of inserting a vein of ironic doubt in the realm of "modernity" as offered by museum exhibitions, by devising pictures in which the more or less imaginary rooms of museums and their works are reduced to sketch cards.

G.V . I am influenced by expectations. I'm trying to recall the reasons why I have always regarded your works in a different way to today, and to ask myself why I now see them in this different light. The things I ascribe to you - not so very arbitrarily, if you don't find them shocking - are also the result of the fact that you've produced works of this kind. Believe me, it's not that I'm now setting off with you in search of someone that may seem a painter appropriate to this Stimmung, this frame of mind, it's simply that works have destinies and hence I get the impression one can really read all this into them. One could then discuss if and how far there is not only, as it were, the surface of a good artifice, a well-turned piece of work, but also an extra recollection, a crumb of tragicality comprised, not ignored, yet not even ironically transcended, simply, affectionately included as at least a slice of life.

U.N. There are slices of life virtually whittled down to the state of "picture cards" in my works, as you can see.

G.V . The reduction of real elements to picture cards, you know, is not just playful schematizing. You can primarily regard it as perception of an object as a trace element, a residue, if you like. When you give the title "Museums" to a series of pictures, I think you realise that a museum holds something more than the art from which you ironically want to stand aloof. There's also the set of monuments of our tradition that you make the subject of not only impish representation. Take one of these "Museums" you're exhibited in Milan. What is very interesting is the distancing of this pinacothèque, reproduced and then thought out again, this perspective standing off is more than the simple placing side by side of all the formal values of a simultaneous museum. Here it is not simultaneous, we have the simultaneity of a set of traces that form layers. The arches and rooms are there, and they undergo a sort of stratification, one on another.

What I am saying is that this reduction of objects to picture cards implies affection, a sentiment never aroused by monuments as such. We feel affection for monuments that are traces of life that can also be felt as mortal. So, I don't think it's very arbitrary to see in all this the materialisation of that fake, arbitrary essence of Rococo I mentioned earlier.

There's something beyond the tragedy that bursts at a certain point, there's a tragedy restrained not because it is known to be worthless, indeed it is of great worth, because it is experienced by those who have died or are destined to mortality. A work becomes a way of living the experience of mortality in this non-tragic, not totally pathetic manner.

This, of course, must go hand in hand with the element of "strong", vivid colour you inject into your works - an element that could, perhaps, be in contrast with this structure. It is something for which I have no immediate explanation. Personally, it doesn't disturb me, I don't find it in conflict with this interpretation of your work. I just find it hard to explain discursively in the slant I've chosen.

U.N. Don't you think the trace of life always involves some elements of vitality?

The picture cards, what is more, make full use of colour in exaggerated shades as if to remove the fixity of those residues, those schematizations. Perhaps it's a way of animating or resuscitating so as to move towards a sense of immediacy.

G.V . lndeed, that's a good reason for saying that the affection behind your portrayal in your picture cards of the completed tragicality of the object that has been an experience of life implies at least a certain respect for the way of taking things on. And hence for certain immediate appearances, such as colour, which in any event was also among the things the avantgardists most distrusted as an excess of immediacy that night make us forget that appearance is that and nothing more.

Yet the fact that appearance is mortality does not mean that it is only appearance.

Appearance is mortality, hence its worth, for the very reason that it is mortal. This could be the summary of the substance of one of your poetics. For the avantgarde, appearance, being that only, arouses feelings of transcendency and even rejection, of relegation to a lower level, of being placed between brackets. Yet it is on just this that you work so intensely.

What perhaps escapes me, as one lacking an extensive knowledge of the history of contemporary art and the history of art in general, is the extent to which traditional painting techniques survive in your work.'

U.N. The field of inquiry in the last few years has gone well beyond the theoretical rigidity of the avantgarde you were referring to. The new movements, all of them, have delved into the techniques and traditions of painting. As far as I'm concerned, and for the very reason that I have what you've called an affectionate attitude towards my work, I have always included techniques borrowed from the traditional stock. And sometimes we can say I've also employed them for the purpose of being provocative. In a strictly conceptual period, you can well imagine that the use of oils was in itself a disturbing factor, an out-of-place event.

G.V . It could also be that all I observe from outside and immediately conceive of as mastery motivated by an attitude of affectionate attention is also something more, for example a sort of consideration for traditional ways of producing that run the risk of being forgotten.

U.N. And, if you don't mind me saying so, I've deliberately worked with unusual and out-of-fashion materials in a provocative vein.

G.V . True enough, I remember some of your works in America, made out of odd materials, not wood...

U.N. Mother-of-pearl, ivory, silver, ebony. In the middle of the Seventies, I held an exhibition, introduced by Furio Colombo and the one you saw in New York, called "Fogginia", inspired by the work of Gian Battista Foggini, a Florentine artist from the second half of the 17th century in the time of Cosimo III. l' d been struck by his great skill in the use of dissimilar materials, his great eclectism. To be provocative, I completed a series of works with expensive, well-fashioned materials, not only as a tribute to a supposed craft tradition that is not mine in cultural terms, but also as a personal reaction to the poor workmanship and anything-goes approach of much of today's art.

G.V . There is indeed a kind of devoted attention that much contemporary art simply doesn't have. The idea of breaking free from formal traditions has also ended up by sending off the field many features that deserve to be kept in mind. Indeed, l' d go so far as to say that one of the criteria I feel I can most

readily apply, privately, if you wish, in assessing works of art is that of how far they evoke one of the traditional techniques. I'm not much taken with the idea of the genius-artist. What I prefer is not exactly the idea of the craftsman-artist, but that of an artist as the repository of a store of knowledge that he manages to get moving in his work.

This is one of the elements that turn my thoughts back to your work.

U. N. I agree. Much of the original avantgarde and its aftermath is marked by the instigation of an enormous distrust of anything and everything. linked to skill on the part of an artist. What we are witnessing now, therefore, is both the pedestrian repetition of this commonplace in a somewhat triumphant tone in what I call Establishment art, and the rediscovery of skills of a kind, and I don't mean just technical know-how.

G.V . Back to bespoke tailoring, in other words! What a paradox! Yet even today, to borrow the tide of a book by a philosopher I know, there are things "the computer can't manage to do", a whole heap of things that, try as you will, cannot be boiled down to repeatable and hence reproducible formulae. So, it's worth rediscovering techniques, even those that are apparently least functional, more traditional if you 1ike, more precious, more tied up in a whole series of traditions, including those we thought we'd said goodbye to for ever. Mother-of-pearl, for crissake! The first thing that word brings to mind is my aunt or my grandmother. Something made of mother-of-pearl is... words fail me!

U.N. And I find it congenial for that very reason. It's undefinable, it doesn't fit in with the rules of the game. There's no mother-of-pearl in this exhibition. But there's the same, identical belle intolerance, what you could call my vocation.

(From the book: Ugo Nespolo, Palazzo Reale, Arengario, Milano, 1990, Electa, Milano)

(From the book: Ugo Nespolo A fine intolerance, Borghi & Co. New York, 1992)