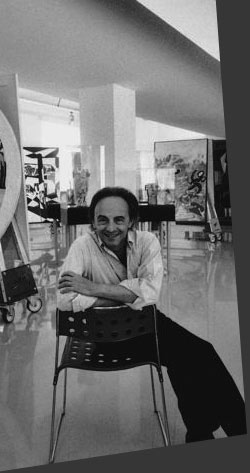

Pierre Restany

UGO NESPOLO AND THE CRITIQUE OF PRATICAL REASON

Ugo Nespolo's universe is one of objective reconstruction. In his constructions, in his «camouflages» (objects covered with speckled painting) or in his puzzles (shapes cut out of flat surfaces) that may be disassembled, one finds the common denominator of his world view: a consciously fragmented approach to reality by means of a succession of planes. Nespolo's reality does not affirm itself as an immediate revelation, enlightening and al I-encompassing; rather, it appears like a thin, intermediate zone halfway between the singularization of the object and its direct appropriation.

We enter a world whose elements have been previously and carefully liberated from all those criteria of generality or universality, upon which common value judgements are usually based. Nespolo's shapes and objects are living at the conditional, not at the indicative mood. They do not affirm themselves or their existence as such. Rather, they suggest a potential time-space dimension. Once integrated inside this dimension, they will take on all their meaning. This ideal context may be spiritually recreated by the onlooker.

However, this effort of active reconstruction is not indispensable; besides, not everybody can enter this laboratory of the mind where the onlooker becomes demiurge. Therefore, the passive onlooker will be open to the «mystery» of the object, the full availability of the shape. This telephone, for instance, might transmit messages. But the connecting wire between the set and the transformer needs no real electrical current to justify its own being: his task is pointing out his own full objective availability to electrical signals, i.e. the possibility of current flow. The same may be said for the «machine for lifting air up to the desired height » made of plastic hoses that may reach up to a hanging reservoir, for a maximum length of 13 feet. And the same applies to the «encumbering machine» I.E. a giant reel resting on a stand and I ready to roll out into space its 160 feet of plastic cloth.

All these conditional machine objects draw their semantic origin from those puzzles Nespolo had turned out in 1966 and that he had significantly chosen to call decomposable» objects and walls. They were made of magnetic puzzle components that one could either fit into a panel or leave decomposed. Here the emphasis was on availability, on the potential quality of the arrangement.

The final result, the composite yet unitary picture, was of little importance. Be it a sketched-out contour or a heraldic blazer (N for Nespolo, surrounded by Napoleon's laurels), what did and does matter is their making the onlooker receptive to the tangible possibility of moving and re-arranging formal elements, leaving him absolutely free to participate.

On the other hand, some objects made in 1966 were only pseudo disassemble, i.e. their structure suggested a puzzle, but the parts were fastened in place. Nespolo has given his objective shapes a conditional freedom: the freedom of our will, once we are conscious of our role in this universe of the language. Lt seems to me that one example does explain the subtle flexibility of Nespolo's situation making. A certain «extensible-decomposable» object, made in 1967, is composed of two open cubes that may interpenetrate. One of them also contains 60 feet of nylon rope. Therefore, the same object is a perfect prism when closed; we might call it a fundamental structure. When open, the two cubes, connected by the nylon rope may be set in countless relationships of situation.

This young artist, with discreet and inexorable self-assurance, yet with no useless ostentation (and therefore with real mastership), indicts the who le system of our rational means of communication. Some find humour in this give and take between subject and object, in this progressing from perception to participation.

Surely, there is humour in this attempt to subdue objective language to the quanta of individual determination and probability calculus. But this humour, so deeply rooted in the language, is its very key, somewhat like an optative mood, announcing the whole virtuality of the message.

Demystified by our smile, the object is readily restored to the original task of « letting the current flow ». Here is an aesthetic philosophy directly connected with the morals of free will. One cannot help thinking of Kant, but a different Kant, totally dedicated to the critique of practical reason.

(From the book: Macchine e oggetti condizionali, Galleria Schwarz, Milano, 1968)